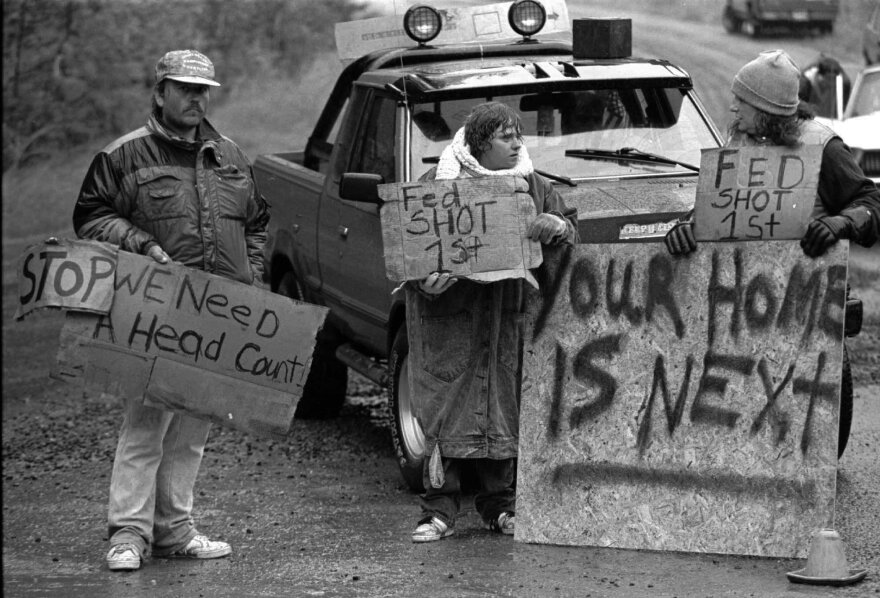

The armed standoff between anti-government militants and law enforcement in Oregon has lasted more than four weeks. After the arrest of 11 people last week, it was expected that the occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge would come to an end, but the killing of the group's spokesman in an encounter with police has re-energized protesters.

We have been here before. Back in the 1990s, there were several showdowns between armed anti-government extremists and the federal government.

One of the longest standoffs involved the Freemen of Montana in 1996, who held out for 81 days before surrendering peacefully to law enforcement. It was a different story in 1993, when the standoff with the Branch Davidians near Waco, Texas, ended with the deaths of at least 75 people — many of whom were children — in a fire.

But it was the events at Ruby Ridge in Idaho that would become the symbol of government overreach. This week on For the Record: the lessons of Ruby Ridge.

"Ruby Ridge is a complex case," says Jess Walter, author of the book Ruby Ridge: The Truth and Tragedy of the Randy Weaver Family. In 1992 he was a cub reporter for the Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Wash. "It's one of the reasons when it first unfolded in 1992, it slipped beneath the radar of the national media and the public."

As he tells NPR's Rachel Martin, the story begins with Randy Weaver and his family.

"He lost his job at a tractor farm in Iowa, and they made their way west," Walter says. "They were apocalyptic Christians who believed the world was about to end. And they began practicing a form of religion called Christian identity, which is the religion of skinheads and white supremacists."

One summer, Weaver took his family to a camp run by the Aryan Nations. He sold two sawed-off shotguns to a man he met at that gathering, but that man turned out to be a federal informant. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms planned to use the illegal weapons sale to recruit Weaver as an informant, as well.

As Walter tells it, the ATF approached Weaver and threatened him with prison time and the loss of his farm. But Weaver, who believed that the world would end because of government treachery, took the threat "almost as a declaration of war," Walter says.

For the next year, Weaver and his family holed up in their cabin on Ruby Ridge, refusing to appear in court to face the gun charges. Federal agents kept them under surveillance.

Everything culminated on Aug. 21, 1992, with six U.S. marshals on the ridge outside the Weaver compound.

"It was very, very thick foliage," remembers Arthur Roderick, who was one of the marshals. "I mean, it was August on a mountaintop. You could barely see your hand in front of your face."

As Roderick describes it, the Weavers' family dog saw him and his partners in the woods and started barking. Roderick says the Weavers' 14-year-old son Sam and family friend Kevin Harris started chasing them. Both Sam Weaver and Kevin Harris were armed. Roderick was carrying an M4 assault rifle.

Another marshal, Bill Degan, told them to stop, Roderick says. Degan announced that they were U.S. marshals.

"This was all happening very quickly — within seconds, you know," Roderick says. "The dog stopped, turned around, looked at me. And then I fired a shot at the dog, which killed the dog right there. And then it was just gunfire for about 20 to 25 minutes."

One of Randy Weaver's daughters, Sara, was 16 at the time.

"I do — I remember hearing the gunshots," she recalls. "I remember being very upset when I heard the gunshot because I wasn't expecting that. I'll never forget feeling panicked and helpless that I wasn't there to protect [Sam]."

When the firefight was over, both the marshal Bill Degan and Sam Weaver were dead.

"I think our family was still holding out hope at that point, that because Sam had died, someone would try and verbally contact us to talk about what had happened or how to resolve the situation," Sara Weaver says.

But journalist Jess Walter says poor communication between federal agencies had been making the situation worse.

"The FBI is getting information on this case from the marshals. They aren't told Weaver's son has been killed. They aren't told there's some question about who fired first. They're only told that some marshals were in the woods surveying Randy Weaver, possibly to arrest him, when he and his family attacked them and killed a U.S. marshal," Walter says.

The FBI flew in a hostage rescue team, but the agency had suspended the normal rules of engagement, Walter says. As he recounts, the FBI told their agents they were going into an active firefight, authorizing them to open fire without warning if they saw an armed adult.

Meanwhile, the Weavers and Harris had put Sam Weaver's body in an outbuilding.

I was so drowning in grief. I pretty much felt that I didn't have a chance of coming out alive.

"They go to check on the body. And as Randy Weaver reaches up to open the shed door, a shot rings out from the woods, and he's shot in the shoulder," Walter says. "And the family run back to the cabin. His wife, Vicki, holding their baby, throws the door open, screams 'Get back in the cabin.' And the FBI agent fires again. And this shot hits Vicki Weaver in the face and kills her."

Randy Weaver, daughters Sara and Rachel, baby Elisheba and Harris holed up in the cabin for the next 10 days, scared that if they left the cabin, they would be shot.

"I was so drowning in grief," Sara Weaver remembers. "I pretty much felt that I didn't have a chance of coming out alive."

She had lost her brother and her mom — but after a harrowing 11 days, the standoff finally ended and Sara Weaver did come out alive, along with her two siblings, their father and Harris. Ultimately, Randy Weaver was acquitted of every major charge because the jury ruled that the original weapons charge against him had been entrapment.

Walter says the fallout from the incident derailed the careers of several federal agents. There were congressional hearings and government reports examining what went wrong. "It really changed how law enforcement dealt with groups like this," says Walter.

Arthur Roderick retired from the U.S. Marshals Service in 2008. He says he thinks of the experience often, but not the Weaver family.

"I try not to think about them at all," Roderick says. "I mean, all they had to do was show up at court. Very simply, that's all they had to do. I think again more about Bill Degan and his family, his two boys, his widow. You know, his mom and dad. That's who I think about."

Sara Weaver lives in Montana now. She works as an advocate for trauma victims and is raising a teenage son.

"There's a lot about him that is so fun and reminds me a lot of my little brother," she says. "I lost him when he was 14. My son is at that 14-year-old age mark. It's been so healing to have that joke-around relationship with him like I had with my little brother. [I] have a chance to be the best mom I can be for him."

Sara Weaver says she's been thinking a lot about Ruby Ridge these last couple weeks as the standoff in Oregon has unfolded.

"This situation is very, very different in many, many ways. But at the same time, I can relate to much of the emotion surrounding it. It brings back my own emotions surrounding it. I just don't want to see people hurt. I know what it feels like, it's devastating — on both sides," she says. "Nobody wins."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.