To consider the dangers in America's future, let's go back more than 2,000 years to ancient Greece. Sparta was the established power, but Athens was rising fast. Sparta wanted to preserve its status, while Athens felt it should be dominant.

The result was a disastrous conflict that ravaged both sides in the Peloponnesian War. The fifth century B.C. writer Thucydides, a resident of Athens, summed it up this way: "It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made the war inevitable."

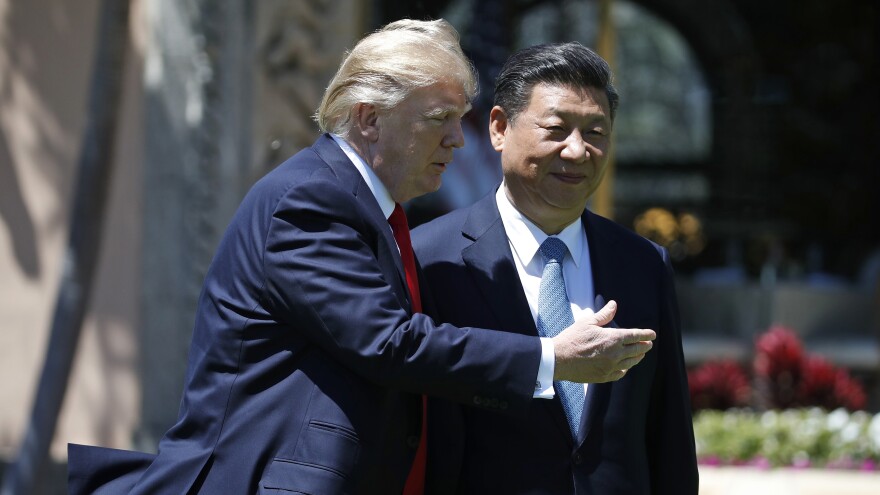

Political scientist Graham Allison, a professor at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government, says this insight remains as relevant as ever. It's only the players that change. Today China is rising, while the U.S. is the reigning superpower.

Allison puts it like this: "When a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power, stuff happens. Bad stuff. So alarm bells should sound — extreme danger ahead."

Allison calls this the "Thucydides trap." He made a splash with this idea a couple of years ago and has a book coming out this month called Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?

At a recent event in Washington, he stressed that war between the two powers isn't inevitable. For starters, no prominent figures in either country sees it as a viable option to solve any of their disputes.

But history is littered with examples of countries stumbling into unwanted wars that quickly spiral out of control, Allison notes.

Consider World War I, where a seemingly local event — the assassination of an Austro-Hungarian prince in the Balkans — sparked a conflagration that cost millions of lives and pitted a rising Germany against the leading power of the day, Great Britain.

"Under this structural stress, incidents or events, that might otherwise be inconsequential, or manageable, turn out to be capable of triggering a cascade of consequences, at the end of which, Europe is totally at war," Allison said.

He has studied 16 cases of rising powers challenging ruling powers over the past five centuries. In 12 of those, the result was war. In the other four, major conflict was avoided — but only with concessions by both sides.

Today he has his eye on North Korea and its nuclear program, calling it "the Cuban missile crisis in slow motion."

More than 50 years ago, Allison authored a seminal analysis of the decision-making during that 1962 crisis, in which the U.S. and the Soviet Union almost went to war — possibly nuclear — when the Soviets placed missiles in Cuba.

North Korea is now working on a missile that could reach the U.S., a goal it could achieve at some point in Trump's term. The president says he won't allow it and has warned of possible military action.

But a U.S. strike would rattle China, which has long propped up North Korea. Allison says the collapse of the North Korean regime could create a mad dash between the U.S. and Chinese militaries to secure that country's nuclear arsenal.

"I think that's one scenario for getting Americans and Chinese fighting each other," he said at a recent event in Washington.

Now, before we go further, we need to issue a disclaimer on grand strategic theories: They're not always right. Not by a long shot.

For example, the world's major powers haven't fought a head-on battle since World War II. So is this trend likely to hold — or is the world overdue for a war between the leading states?

China's President Xi Jinping, speaking in Seattle in 2015, said:

"There is no such thing as the so-called Thucydides trap in the world. But should major countries time and again make the mistakes of strategic miscalculation, they might create such traps for themselves."

Journalist and author John Pomfret has followed China's rise since he first went there as a student in 1980. His recent book, The Beautiful Country And The Middle Kingdom, documents more than two centuries of the U.S.-China relationship.

He believes trade and other ties are a counterweight that's likely to keep the U.S.-China competition from turning into a military conflict.

"That integration, and it's not just economic, it's also cultural, educational as well, I think that mitigates, significantly, against this idea that, 'Oh, conflict between these two great powers is inevitable,'" Pomfret said.

Still, Thucydides has shown remarkable staying power as a military analyst.

Trump's national security adviser, H.R. McMaster, cited the ancient Greek historian in a talk last November in Washington.

"In the 1990s, it became conventional wisdom that future war was going to be great. It was going to be fast, cheap, efficient," McMaster said. "It didn't acknowledge war's enduring political nature — the fact that people fight for the same reasons Thucydides identified 2,500 years ago: fear, honor and interest."

Greg Myre is a national security correspondent. Follow him @gregmyre1.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.